The Humboldt Mill: A Brief History

- kelseyboldt

- Apr 5, 2024

- 4 min read

People will wander into the Eagle Mine Information Center in downtown Marquette to find out more about the operation. Inevitably, they will be led over to a map that shows the distance between the mine and the mill and the truck route to and from. 66 miles in total. The visitor will look at this and ask if we have ever thought of building a road that would cut the journey by more than half. Others ask, better still, why we wouldn’t just build the mill right next to the mine.

Valid questions. Both of them. Often the simple answer is that the shorter road was thought of and didn’t pan out. Plus, the mill was already there so the permits were much easier to come by for a brownfield site vs. breaking ground on a greenfield site.

That’s only part of the story, though.

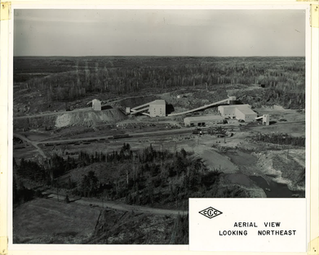

The area where our mill is today has a long history of iron ore mining dating all the way back to the 1800s. Several mines, like the Washington and Edwards open-pit mines, were located there. The Humboldt Mill and some of the original buildings and machines, however, had its first incarnation in the 1950s when Cleveland-Cliffs Inc. built the mill to process ore from the adjacent Humboldt Mine. The Humboldt Mine was an open-pit iron ore mine that ran from the 1950s until the early 70s. The mill also processed ore from the close by Republic Mine. Even when they stopped mining iron ore at the Humboldt Mine, the mill kept processing ore from Republic.

The mill ran until the late 1970s when the Republic Mine shut down. For a time, ownership of the mill frequently changed hands and only portions of the facility were used intermittently. Eventually, ownership of the Humboldt Mill site landed in the hands of the Callahan Mining Company. Callahan refurbished and used the mill to process gold from the newly reopened Ropes Gold Mine.

The Ropes Gold Mine site, located near Deer Lake, had a legacy of its own. Ropes Gold started operations way back in the late 1800s. Nearly 100 years later, the operation started back up again in 1984 and breathed new life into our beloved Humboldt Mill to process gold until 1990.

By the late 1990s, however, the mill was no longer in use and aged into disrepair. Interestingly, Humboldt Mill’s interlude coincides with the beginning of Eagle Mine’s story. The two sites would become intertwined in the years ahead.

Flash forward to 2008 when Rio Tinto bought the mill and over the next 3 years obtained the necessary permits for refurbishing the mill and setting to work on its restoration. The whole process cost $275 million and included not only the work of bringing the mill back up and running, but also environmental reclamation of the surrounding area which had been contaminated by mining refuse. This process started in 2011.

During the gold processing era of the mill in the 1980s, cyanide was one of the main chemicals used to extract the gold from the ore. A large part of the environmental reclamation of the site was cleaning up the cyanide contamination at the plant. The inside of the existing plant was triple washed with high pressure water, the runoff water was collected and treated, and the building was sealed with paint. The outside was replaced with new cladding. Brandenburg, the company leading the cleanup, completed this sensitive work with zero recordable injuries – an incredible feat.

Another part of the cleanup involved treating contaminated soil. Piles of iron ore concentrate, iron ore pellets, and pyrite concentrate sat on the ground for years near where our railyard is today. The process of cleaning up such an area included removing the concentrate and pellet piles and then excavating the land to 4 feet deep. Fresh topsoil was used to cover the excavated area so that water would run off the surface through clean, fresh soil.

Construction on the mill and equipment upgrades began in 2012.

The ball mills, or at least some of the main components, are from the original mill constructed in the 1950s. The foundations, anchor bolts, and trunnion bearing housings (a trunnion is a cylindrical mounting or pivoting point) are all original. The original motors were re-wound for current use in the mill as well. However, the shells, or the rotating drums, are new and were constructed to fit the existing foundational structure. The original shells are still intact and kept at the Humboldt Mill today, but the wear and tear on them was too great to justify reuse.

While other buildings, including our mill Coarse Ore Storage Area (COSA), are unique to the Eagle era of the Humboldt Mill, another original component from the mill of the 1950s is Conveyor 5. The entire steel structure and the rollers are original to the mill. The original primary crusher building still stands on the hill behind our COSA. Though it is not used in our process today, it remains a repository for historical core samples from both Humboldt and Ropes mines.

Though much more of the original mill was intended to be reused, as the process of restoration went on, it was obvious that the pyrrhotite contained in our ore was a concern. When pyrrhotite, an iron sulfide mineral, is stagnant it will self-heat and could potentially cause a fire. The existing process in the mill had areas of stagnation and thus bigger changes were implemented. Mainly, the original fine ore bins were replaced with mass flow bins, and the mill feed systems were replaced with updated designs to ensure the safety of the new mill.

Eagle Mine will celebrate its 10th anniversary of full operations this summer. Such a milestone invites reflection. The mill is a natural place to start as its vast history far exceeds the making of Eagle Mine’s history. And it is an important reflection. Eagle Mine’s restoration and reclamation of the historic Humboldt Mill site gave the plant a chance to remain a viable and important part of the local economy even after Eagle closes. The mill’s potential is one of its best features, and looking back on its past can help us contextualize the future.